What would you say to an aspiring scientist?

“The most important thing is to come as you are. I think a lot of scientists of my generation and older had to sacrifice a lot of who they were in the name of professionalism, and I think when you swallow who you are as a person it takes a mental toll… I think that’s why it’s really important to openly be who you are, so that you can actually put your focus to what you really want to do, what you’re really passionate about, which is the science in front of you. And when you do, that is again going to inspire someone else who can say ‘look at that person who’s being completely authentic in themselves–I can do that too.’ ”

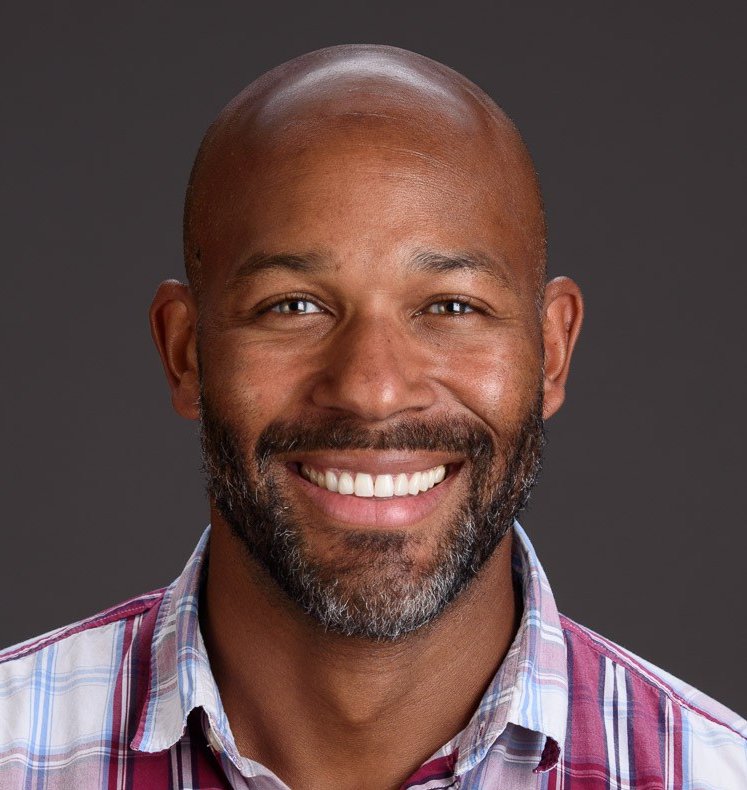

“Where do baby ducks come from? What species of snake is this? What do they eat? Is it poisonous?” Dr. Derek Applewhite wondered these questions to himself while growing up on a farm in rural Colorado. Spurred by his proximity to all kinds of domesticated and wild animals, from horses to chickens, rabbits to ducks, his fascination with the natural world bled into lifelong scientific curiosity.

Derek, now an Associate Professor of Biology at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, recalls his curiosity being well “fed” by his parents, both educators in non-STEM fields. They recognized his enthusiasm early, encouraging him to explore science through monthly visits to the Natural History Museum and supporting his quest to take every science class available to him in high school.

The love of science never left him, going on to study biology at the University of Michigan for his undergraduate degree and then joining the lab of Dr. Gary Borisy at Northwestern for his PhD in cell and molecular biology. Derek describes his career trajectory to his current position as an Associate Professor of Biology at Reed College as “atypical.” While doing a postdoc under Dr. Steve Rogers at UNC Chapel Hill, he felt particularly dispirited by the process of finding his next career step. He had been in his postdoc position by then for 6 years, and recalls thinking, “This is all I’ve ever wanted to do, so I don’t have a backup plan. All my eggs were in this one basket [of becoming a principal investigator (PI)].”

“This is all I’ve ever wanted to do, so I don’t have a backup plan. All my eggs were in this one basket [of becoming a principal investigator (PI)].”

When Derek was 16, he joined the Science Motivation Program at Colorado State University, a summer program for minoritized students interested in science. He worked on finding the optimal thickness for bone cement for hip reconstruction in dogs, working with a veterinary orthopedic surgeon and a graduate student in biomedical engineering. The collaborative nature of the project enthralled him and he recalls that experience as the first time he seriously considered becoming a research scientist.

Derek applied to a position at a liberal arts college in Portland, Oregon, was selected as one of the finalists, but ultimately didn’t get the job. Serendipitously, another liberal arts college in Portland was just about to start its own search for a Cell Biology professor when they learned about Derek. A Reed Biology professor heard about his engaging cell biology research from a colleague and the department reached out to Derek shortly after with an offer for a job interview. He recalls being confused, “I don’t understand, I didn’t apply, you’re approaching me to apply for a job?” It was a strange but lucky experience, especially because the dearth of PI positions makes the process of getting a job as a PI anywhere incredibly difficult. Ultimately, Derek feels thankful for how things turned out, appreciating that Reed’s support of both student and faculty research means that he gets to continue working towards understanding the microscopic skeleton of the cell — the cytoskeleton.

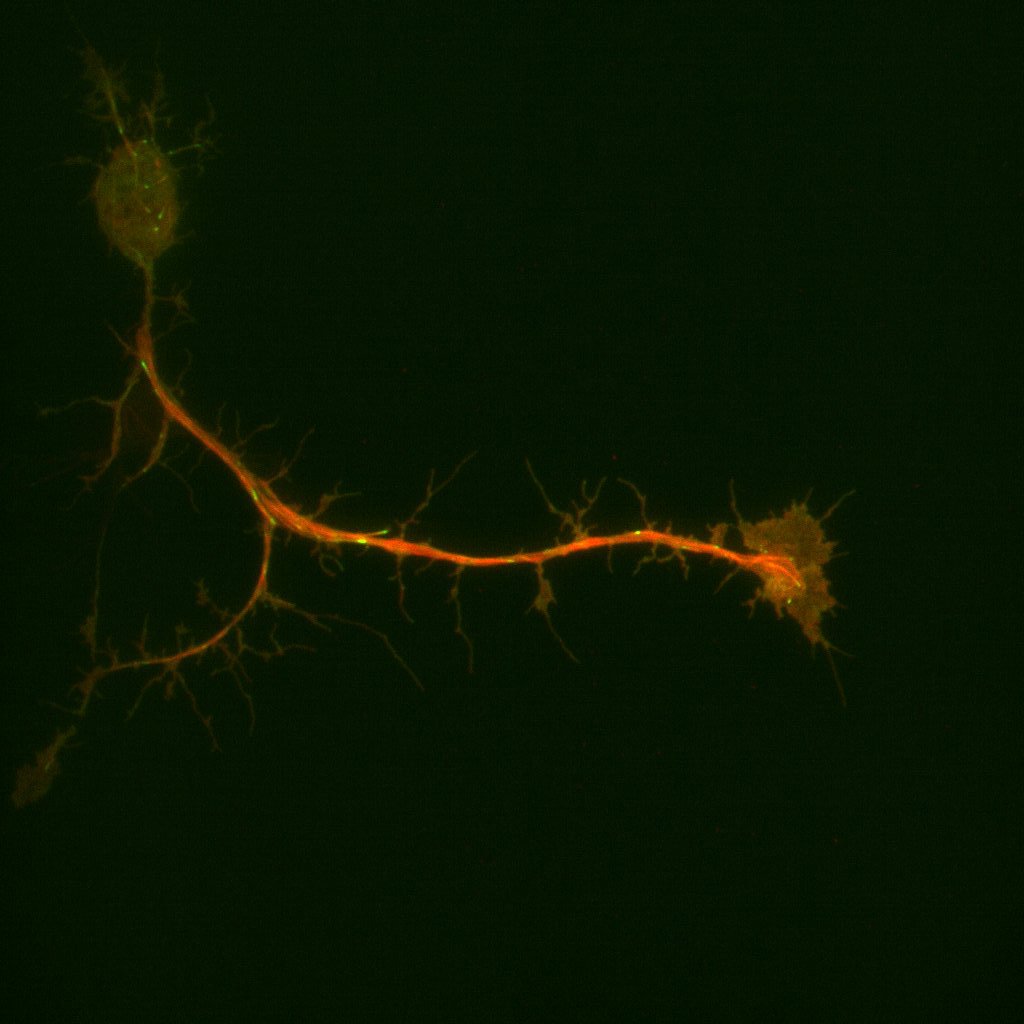

image of fruit fly cytoskeleton from Derek’s lab

“If you find yourself hating everything about what you’re doing except for what you’re doing at work, that’s actually not a good place for you. Life outside the lab is equally as important as life in the lab.”

Derek’s research focuses on understanding how the proteins that make up the cytoskeleton help cells move and change shape, for example when you contract or expand your muscles. When proteins in the cytoskeleton don’t function correctly, a person will have trouble moving their body, like in the neurodegenerative disorder amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Outside of the lab, Derek continues to love the natural world, especially the wonderful hiking opportunities in the Columbia River Gorge, just outside of Portland. He emphasizes the importance of enjoying life outside of science, noting, “If you find yourself hating everything about what you’re doing except for what you’re doing at work, that’s actually not a good place for you. Life outside the lab is equally as important as life in the lab.”

Many of his students use powerful microscopes to take beautiful images of fruit fly cell cytoskeletons as they change shape and move. Overall, Derek says the interdisciplinary nature of cytoskeletal biology makes it endlessly fascinating for him, involving biophysics, computational biology, modeling, and of course, microscopy.

Even though the scientific questions at hand were consistently captivating, the surrounding academic system wasn’t always as functionally supportive. “It was really hard to go through undergrad and grad school, and even as a postdoc, never having a Black professor, never having an out gay professor that I worked with,” he says.Derek describes that a common response to this lack of representation is to “swallow” aspects of yourself and to sacrifice important parts of your identity in an attempt to blend in. Yet for members of the LGBTQ+community, spending energy on the mental gymnastics involved in swapping pronouns in conversation to conceal indicators of sexual orientation takes a mental toll. Code switching, or altering your language, appearance, or behavior in order to receive equal treatment as non-minoritized peers, is taxing. Extra mental work spent making sure you’re presenting “the right way” takes away time and energy from actually doing science.

“It was really hard to go through undergrad and grad school, and even as a postdoc, never having a Black professor, never having an out gay professor that I worked with.”

In grad school, Derek sometimes saw other Black or LGBTQ+ scientists at national meetings, but this diversity wasn’t present in his daily scientific experience until he met his now long time mentor and friend, Dr. Omar Quintero (Professor at University of Richmond). Omar, then a postdoc, was always showing him what grants he was writing, what he was applying for next, and provided a lot of day to day advice as a slightly more senior Black scientist. “He was one of those people that was always looking back, lending a hand, and pulling me up along with him.”

Now as a mentor himself, Derek embodies that supportive mentorship style. He keeps in contact with many of his undergraduate thesis students after they leave Reed, trading emails and helping them however he can. He notes that a reminder that a mentor is in their corner and cheering them on can be all someone needs to hear.

Derek emphasizes the importance of clarifying the “unwritten” aspects of academia—the little details of academic culture that are never formally explained, especially for students from minoritized backgrounds. Thinking on past scientific roadblocks he remembers never knowing if his failure to receive a grant or publish a paper was because his science really was deficient, or because of his personal identity. Looking back, he sees the microaggressions, little misses that make one wonder, ‘Was it me? Is this my fault? That must not have been good enough.’ Eventually, it becomes clearer that implicit bias impacts interactions with other scientists, as well as grant and paper decisions.

Unacknowledged biases in the scientific community are particularly pointed now that social media has made personal information so easily accessible. Anyone, including reviewers, can look you up and see what you look like in seconds. Derek wonders, “How do you take in this information and not actually use it when you’re reading or reviewing something? You can’t, because we’re human. It’s insidious because it’s so covert.”

“Every diverse voice that is added to science is making it better, so just know that your voice does really matter, it does count, and it’s helping all of us in the community continue to get better.”

Reflecting on the past year, Derek remains cautiously optimistic that there is finally traction for real change regarding systemic racial biases, both in the scientific community and in society at large. “2020 has been a wild year,” Derek says. “Obviously with the pandemic, but also because with George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, [awareness has] trickled down to all areas of society,” noting that time spent in quarantine also amplified the message and kept people’s attention from drifting. He believes that everyone, including young scientists, is realizing they aren’t powerless, and is learning to advocate for themselves and others.His parting message is a call back to the importance of speaking out, helping each other, and coming as you are: “Every diverse voice that is added to science is making it better, so just know that your voice does really matter, it does count, and it’s helping all of us in the community continue to get better.”

by Elizabeth Pekarskaya